Congressional District 4’s ‘Town Hall For Our Lives’ Continues the Conversation on Gun Reform

Image via Bryden Smith

Many arrived early to the “CD-4 Town Hall For Our Lives” event at the Douglas County Fairgrounds Barn in Castle Rock, Colo. on April 7. Soon after discussions began, empty seats were filled and some attendees stood in the back.

“No firearms allowed,” read a sign outside the entrance to the Douglas County Fairgrounds Barn in Castle Rock, Colorado, on the afternoon of April 7. Inside, potential local representatives gathered together with community members for the “Congressional District 4 Town Hall for Our Lives,” an event centered on continuing the conversation on gun reform following the Parkland shooting and its resulting political advocacy.

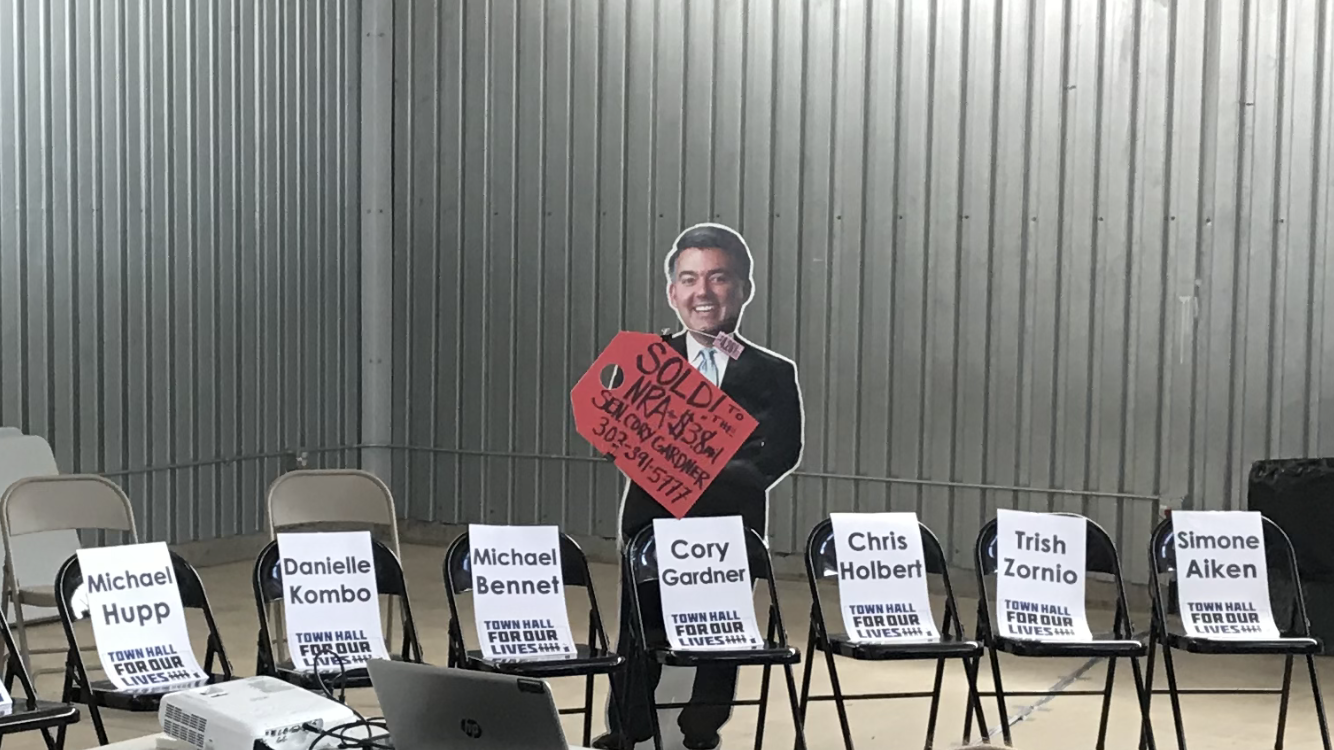

Just like the “March for Our Lives,” “Town Hall for Our Lives” events took place all across the country, with invitations sent to running and elected representatives on both sides of the political spectrum. Chairs for those who were invited but didn’t attend were intentionally left empty.

Before things in the barn got started, attendees conversed with local advocacy groups like “Moms Demand Action” and “Colorado Ceasefire” as well as some local candidates who arrived early. Soon, hosts Isaac McCorkle, an ex-marine, and Katie Lea, a student-activist from Legend High School, kicked things off.

“We need to start building community,” McCorkle said, before introducing Tom Mauser, who gave a short introductory speech. Mauser lost his son Daniel at the Columbine shooting and has been a gun-control activist ever since.

By the time he had finished, all of the political figures who decided to attend had arrived, taking their assigned seats beside the projector screen at the front of the barn, ready to answer questions submitted by students in the area. Those who were physically present — including Tim Krug, Julie Sarjeant, Chase Kohne, Karen McCormick, Michael Hupp, Danielle Kombo, Simone Aiken and Trish Zornio – appeared to share a similarly positive mentality on gun reform and all plan to run in upcoming elections.

Debora Scheffel, Kim Ransom, Patrick Neville, Chris Holbert, Ken Buck, Cory Gardner and Michael Bennet were also invited, but their seats sat empty. Behind the chairs of Buck and Gardner were large cut-outs of the men, depicting their involvement with the National Rifle Association.

The political alignment of the speakers resulted in an event with a partisan tone; most questions asked were answered almost unanimously. Instead of debating whether gun reform was necessary, the most productive conversation was centered around what legislative measures would best curb gun violence.

One comment from a 10-year-old student at Frontier Valley Elementary prompted some disagreement. “They make us do drills,” the child wrote, “but I don’t know what a gunshot sounds like, or how to defend myself, or even if I can.”

“When I was a kid, we did drills for tornadoes,” responded Kohne, who’s running for Congress. A major in the Army Reserves, Kohne went on to say that there is value in proper training, even though it’s heartbreaking that it’s needed. Aiken, however, disagreed.

“Drills give us the illusion of doing something,” Aiken said, explaining that “insiders,” or potential shooters who are students at the school, receive the same training and in turn know how to combat it. She brought up the fact that the Parkland shooter’s knowledge of drill procedures made his attack especially lethal.

Another topic met with mixed responses was the idea of armed student resource officers in schools. While Hupp insisted that their presence increased school safety, Kombo argued that students of color are disproportionately affected by the officers when it comes to disciplinary actions.

Other ideas explored were met with applause from the audience each time they were brought up. Proper storage of firearms, a better ownership registration system and mandatory waiting periods were frequently mentioned. But none came as close in conversational frequency as the possibility of red flag laws, which allow for firearms to be removed from the hands of those who might be a risk to themselves or others.

As discussion surged on, talk turned to the Second Amendment.

“It wasn’t just arming the people, it was disarming the government,” Aiken asserted, pointing out the original ban on standing armies and the many advancements in military technology that extend beyond the scope of guns. Nowadays, “a common citizen cannot have the height of military technology,” but that was different in 1776, she said.

After an hour and a half of discussion, it became clear that those who were in attendance are more than just civically engaged – they’re hurting. When the projector displayed the victims of the Sandy Hook shooting, Krug wiped tears from his eyes. When McCorkle spoke of his close friend and fellow marine who had committed suicide with a gun, he had trouble getting the words out.

The audience didn’t ask questions up to this point, but one woman in the front row, elderly, with dandelion-white hair, asked for the microphone.

“No guns are allowed in the capitol. No guns are allowed in the White House…” She paused, and with welling eyes, she pleaded: “Why?”

The “CD-4 Town Hall for Our Lives” concluded with more emotion, as Lea took the microphone for herself. She told the story of Donna Royer’s death in 2011, which touched many in the Parker community. Then, she spoke of personal experience.

“It’s not okay that I was taught to lay down, spread my dead friend’s or teacher’s blood on me and play dead in elementary school,” Lea said. “We know that we wouldn’t stand a chance against an assault rifle.”

Bryden Smith believes in the news. But at the dawn of the age of information, he watched as technology became ingrained into peoples’ lives at an exponential rate. The media is struggling to evolve, and with a divided political...