Touching or not—prisoners, dogs, presidential candidates

Scraps of grey lint glinted at me from the industrial-strength carpet in a small room in a Colorado prison a few years ago. The ten or so women who usually came to the weekly yoga class that I taught there had yet to arrive. A prisoner whose designated job was to serve as a “porter” offered to vacuum the room, and she helped me set up yoga mats.

The debris that had speckled the carpet before she vacuumed it? “Last night they strip-searched us in this room.”

“Five-minute movement for units one and two,” intoned a voice. The first woman to arrive responded to my pleasantries, “How am I? I’m sick of going to the bathroom and hearing women having sex.”

Everybody knows, goes a song by Leonard Cohen. Everybody knows that the dice are loaded/ Everybody rolls with their fingers crossed.

Everybody who works, visits, or lives in a prison knows this: any sexual contact between prisoners, guards, and volunteers is outlawed (under the Prison Rape Prevention Act of 2003 as well as Colorado law). Many well-publicized ways of reporting and investigating charges of rape are in place in Colorado state prisons—including the prisoner’s right to a victim advocate.

“What does a woman want?’’ Sigmund Freud asked. He called it “the great question that has never been answered, and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul.”

Women–a baker’s dozen or more—have said what they did not want from presidential candidate Donald Trump—groping, grabbing, or otherwise inappropriately or unlawfully touching them. They said he did grope and grab; he says he didn’t-wouldn’t-won’t.

Trump vilifies Hillary Clinton for scrubbing away the emails that were on her private server when she was Secretary of State. He wants to lock her up.

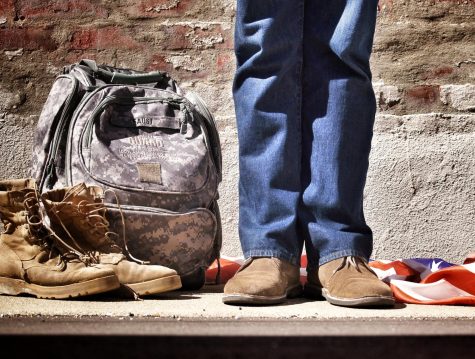

In prison, I’ve been touched by the humanity expressed by prisoners, guards, and visitors. A prisoner has knelt down on another’s yoga mat to console her as she sobbed because her parole had been denied, “It’s all right, yeah it sucks, you’re gonna make it.”

Once as I was going through the metal detector, I saw a guard who was screening a young woman visitor and her baby; the guard gently cradled the infant’s foot while saying hello.

In a prison yard, I once smiled at a woman who was one of a select few inmates who train dogs for pet owners in Colorado. She introduced me to a sleek black Labrador mix who sat when she quietly issued the command.

“Wanna pet Leon?” As I scratched the dog’s ear, she advised, “Move your fingers under his chin like this, so he doesn’t think you’re going to strike him. Now you can pet him.” The dog lapped my hand.

Giving Leon another affectionate scratch, I would have offered to shake the prisoner’s hand—the only form of touch allowed between us, but Leon’s tongue was spreading the love in our threesome.

In this year’s presidential town hall debate, audience member Karl Becker asked the candidates, “[W]ould either of you name one positive thing that you respect in one another?” Clinton cited Trump’s “incredibly able and devoted” children, and he said, “She doesn’t quit and she doesn’t give up.”

Here’s how the two candidates might re-kindle that brief moment of rapport: they would join me in prison for yoga—no staff, no news media, prison guards outside the room as usual. Prisoners and candidates in loose-fitting garb would practice simple postures, one being downward-facing dog, everybody’s buttocks in the air. We would breathe out a few lion’s breaths—each of us sticking out our tongue, expelling fears, doubts, and demons. At the end of class, we’d intone Ommm.

Afterwards, the two candidates would shake hands with the prisoners, and the prisoners would teach them how to shake hands with each other.

Everybody knows. That’s how it goes.