Hitler: The Path to Power

As chancellor, and self-appointed “Führer” (leader) of the German Empire, between the years 1933 to 1945, Adolf Hitler authorized countless acts of carnage throughout Europe. In his name, the Nazi regime persecuted and murdered Jews, Roma and Zinti (gypsy) folk, the ailing, and the disabled. With the invasion of Poland in 1939, Hitler instigated a second world war, which claimed over 50 million lives. But what paved the way for Hitler’s ascension to power? A retrospective glance at Germany a century ago could provide key answers.

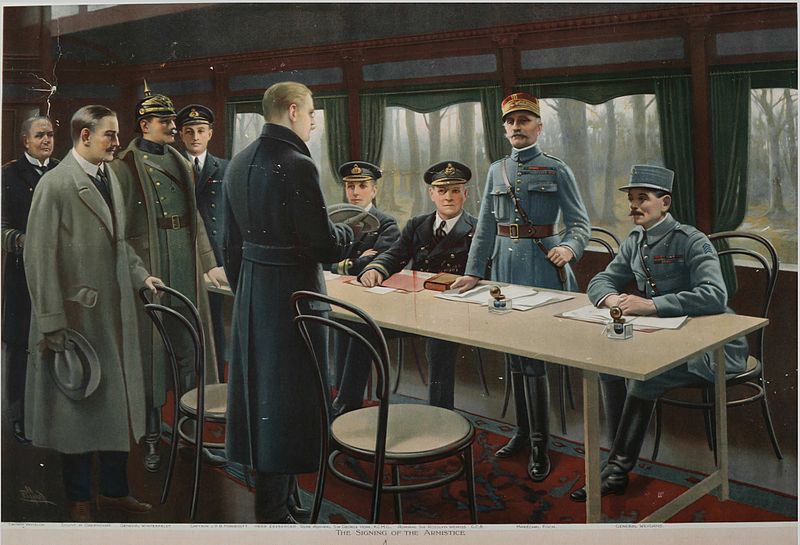

Signing of the November 11, 1918, armistice. Seated from right: General Weygard (FR), Generalissime Foch (FR) (standing), Admiral Rosslyn Wemyss (GB), Vice Admiral James Hope (GB). From back left: Captain Vanselow (GER), Count Oberndorf (GER), General Winterfeldt (with spiked helm) (GER), Captain Marriott (GB), and Mattias Erzberger (GER).

Setting the scene

Germany’s bitter concession to the allied forces in World War One, exacerbated by the humiliating and enduring years thereafter, were consequential factors for Hitler’s seizure of power.

Triggered by the assassination of presumptive heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria (nephew to Emperor Franz Joseph) and his wife, at the hands of a Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo, Bosnia on June 28, 1914, Austria declared war on Serbia.

Meanwhile in Berlin, Kaiser Wilhelm II, ruler of the German empire, with a desperate yearning for turning Germany into a world power, decided to join the fight by declaring war on Russia and France.

Convinced the war would be short-lived, with a swift victory for their Emperor and his army of Junkers, many Germans allegedly jubilated at the outbreak of the war, later described as the “Spirit of 1914.”

By marching into Liege, Belgium – on route to France – Germany inadvertently activated the 1839 Treaty of London, mandating Britain to protect its allies in the low countries (Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxembourg).

Although part of the secret 1882 triple alliance with Austria and Germany, Italy initially maintained a neutral stance—only to side with the Entente (Allied) Powers in 1915.

By exploiting Germany’s heavy reliance on imports, allied forces maintained a stringent naval blockade—spearheaded by Britain’s superior sea power—leaving large parts of Germany teetering on starvation.

The Winter of 1917/18 was particularly harsh. A poor potato harvest the previous autumn meant many Germans had to subsist on turnip rations.

Still, people were stunned when the highest echelon of the German armed forces suddenly offered a cession of hostilities in September 1918.

Inconceivable, given that just months prior, the new Bolshevik government in Russia had signed the peace treaty of “Brest-Litovsk” with Germany, thereby relinquishing vast parts of the Balkans to Germany, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire.

An Ignoble Peace

Many Germans refused to believe in their army’s defeat. Cimmerian conspiracy theories flourished as people sought out a scapegoat.

One such thesis, emanated from the Supreme High Commander of the combined forces, and later President of the Weimar Republic, General Paul von Hindenburg: “The German Army remained undefeated on the battlefield, but was dagger stabbed from behind, by its civilian government.”

The “November Revolutionaries,” who, in 1918, ultimately ushered in Germany’s transformation from monarchy to a republic, had negotiated an armistice even though the war was supposedly far from lost.

Coined as the “Stab-in-the-back theory,” this doctrine resonated well with the people. Particularly, with the young Corporal Adolf Hitler, who, at the time of the armistice lay in a military hospital near Ypres, Belgium, recuperating from a blinding mustard gas attack.

On June 29, 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, allied dignitaries gathered in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, France, to witness the German delegation consent to the terms of the Peace Treaty; effectively ending the Great War.

In addition to shouldering the whole war debt, Germany was obliged to pay reparations in the billions of dollars. A clause in the Treaty warranted the victors to occupy the left bank of the Rhein river for a period of fifteen years. And for safe measure, Germany was only permitted a limited armed force of 100,000 career-soldiers, with one-seventh of its territory excised.

Aghast at the terms imposed upon them, many Germans regarded the Treaty as an Ignoble Peace, referring to it as “The Versailles Command.” But there was no alternative; it had become a fait accompli.

Radical Ideologies

Resentment among the populace grew with time, allowing for radical parties such as the NSDAP—Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party and the KPD—Communist Party of Germany, to take hold. Presenting a platitude of extreme dogmas, their messages became oddly compelling to the masses who longed for political and economic stability.

In 1923, the struggle for political power reached a preliminary peak: The high reparation-payments resulted in inflation. Essentially fleeced for their meager savings, the population was paying for the First World War.

For the NSDAP, headed by Adolf Hitler, this was an opportune time to promote their vision of a “legal” dictatorship to the people. A coup d’etat attempt known as the “Beer Hall Putsch” involving Hitler failed, resulting in his imprisonment, and the completion of his foreboding literary work, “Mein Kampf.”

November 1923 ushered in a new currency reform, diffusing the tense political and economic climate of the nation. International relations were back on track again, with then Foreign Minister Stresemann successfully re-negotiating reparation contracts with the victors of WWI. Moreover, Germany joined the League of Nations.

Nonetheless, the seemingly stable socio-economic conditions in the country proved ephemeral as the New York stock exchange began to free-fall in 1929. This resulted in a global financial crisis, affecting Germany particularly hard. Vital foreign credits remained unrequited, industrial output sank by 40 percent, and six million workers lost their keep. The country suffered a mass economic impoverishment.

Fragility continued to mar the Weimar Republic, enduring ten Heads of Government transitions in as many years.

Anew, the NSDAP was there to profit from the plight of the people. At the September 14. 1930, national poll-elections, the NSDAP secured a substantial 15 percent increase in votes, making it the second strongest faction in the Reichstag (parliament) after the SPD—the Social Democratic Party. Its leader of nine years, Adolf Hitler, emerged as the most viable adversary to the incumbent President, Hindenburg.

Hitler is Elected Reichs-chancellor

In the following years, after the Great Crash, the NSDAP became successful in asserting itself not only on the governmental level but simultaneously with the common people. Their vociferous supporters took the political power struggle to the streets, perpetuating the flames of discontent, still smoldered from the humiliating capitulation in WW1 and the draconian penalties prescribed in the Treaty of Versailles.

By propagating Adolf Hitler as the “Avenger” of the German people, the masses effectively set the stage for Hitler and his Brownshirts to clinch power.

A last-minute attempt by President Hindenburg and Reich’s-chancellor Papen to consolidate Hitler with their objectives ultimately failed. On January 30, 1933, in spite of severe misgivings, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Alois Hitler as Reich’s-chancellor.

Without this official decree, spurred on by fervid public support, Hitler would not have become Chancellor of Germany. In the previous poll-elections held November 6, 1932, the NSDAP secured the majority of votes with 36.8 percent.

With President Paul von Hindenburg’s death eighteen months later, Hitler effectively became Head of State and Head of Government, by merging the offices of President and Reichs-chancellor.

On the eve of February 27, 1933, the German parliament–the Reichstag–went up in flames as a result of arson. Accusing the Communists, Hitler had them swiftly expelled from the parliament before enforcing a national state of emergency, whereby all civic freedoms were suspended.

In one fell swoop, the Nazi party gained control of Germany’s army, its police force, its government, and its economy. Hitler was in full command.

Rashid Mohamed • Apr 18, 2017 at 11:54 am

Hi Janis,

Thank you for your comment. I am pleased to hear that the article provided new information and indeed, I hope you had an interesting conversation with your friends. Hitler and his past still linger in many parts of Europe, especially Austria, where I was born and raised.

You know, I’ve been asked to write a follow up piece highlighting the events leading up to WWII. I plan to do so soon, so please continue to check in on the Pinnacle.

Thanks,

Rashid

janis dailey • Apr 14, 2017 at 7:47 pm

Good Afternoon Rashid,

I came across your article, “Hitler: The Path to Power” and found it very intriguing. The topic of Hitler and his power has been a large part of my historical education. I come from Latvia, where my nation was forced under the hand of Stalin’s dictatorship to fight the forces of Hitler during WWII. However, I never knew how Hitler came to power, but I am very familiar how he used it.

I was influenced by this article to spark a conversation with my friends back home in Latvia. I want to share my new found knowledge with them which I think they will appreciate. We all were taught in the same school, and I do not think that they have accessed any of the information I have learned through reading your article. I would love you to write another article about Hitler and future decisions he made after achieving his power. I was so surprised to hear that Hitler presented him self from the German peoples side. I was always under the assumption that he was a hard driven, no nonsense dictator that only held his ideals first.

Overall I feel this article has challenged me to question the knowledge I have come to know true about Hitler and how he came into his power. Thank you for opening my eyes to the importance of Hitler’s rise to power. Not only through the German national struggle, but also the international impact the great war had on the start and inevitable outcome of WWII.

Thank you,

Janis Dailey

Shannon Alderton • Apr 13, 2017 at 12:24 pm

Hello Mr. Mohammed,

I recently read your article featured in the Pinnacle titled, “Hitler: The Path to Power.” It was very interesting and instructive!

I have always been interested in all things relating to WWII, so I was immediately drawn to your article. However, I have not studied much of Hitler’s life specifically, so I was surprised to learn that he did not start off as a powerful individual. This shocked me, in fact, as I realized how seemingly easy it was for him to rise to power. That being said, do you think that Hitler’s path to power could have easily been prevented?

I look forward to hearing your opinion on this! (I do get extra credit if you respond).

Thank you,

~Shannon Alderton

ACC Student

Rashid Mohamed • Apr 14, 2017 at 9:23 pm

Hi Shannon,

Thanks for reading the article and your kind comments.

The series of events that led to Hitler seizing complete power were fortified by the Enabling Act of 1933. This act gave him the power to do as he liked – without involving the Reichstag (parliament) in any of his decisions. Once he skillfully wiped out his opposition, there was no one to stand in his way. But I suppose the only thing stopping Hitler from attaining absolute power in 1933 was Paul von Hindenburg, then President and Military leader of Germany. Hindenburg, who’s power was waning and misjudged Hitler’s ambition to become Fuehrer, passed away a year later. And once Hitler did become Fuehrer, one of the first things he did was to disregard the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. This would have been enough reason for France and England to reign in Hitler. But the international community gave this man too much leeway which he fully exploited. And finally, if the German army had not pledged allegiance to Hitler and the Nazi party early on, they could have stopped Hitler too.

So, he would not have been easily stopped but with a concerted effort by the other European countries, history could have turned out quite different. Maybe.

If you have any further questions on the topic, Shannon I would be happy to discuss.

Regards,

Rashid Mohamed