Food is uncertain, so is help

ACC examines options to address food insecurity

Image via Rachel Lorenz

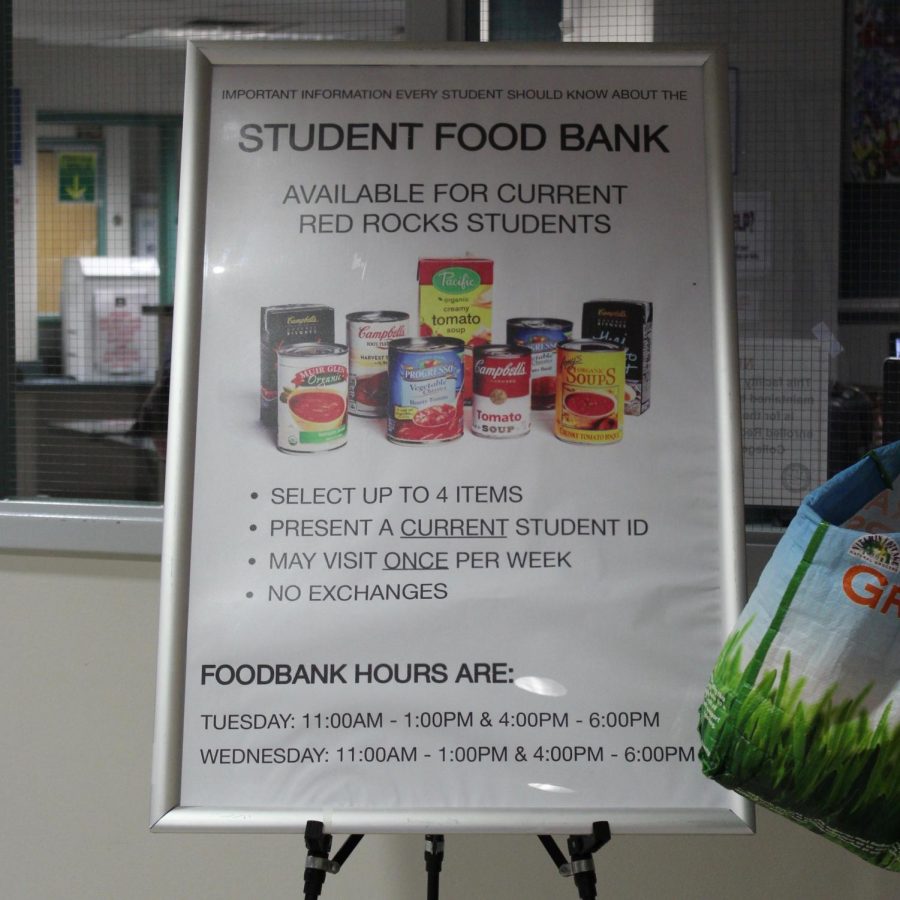

A sign informs students of the food bank’s rules and hours at Red Rocks Community College in Lakewood, Colo., April 18, 2018. Food banks are one way colleges can fight food insecurity on their campuses.

Students hover around computer screens, peer-reviewing each other’s flyers, posters and videos. Professor Scott Guenthner asked his English Composition II classes to create a visual document that addresses poverty at their school, Arapahoe Community College. Three of the posters touch on food insecurity.

“It’s just the [false] idea that if I have a house to live in, or if I’m not starving, then I’m okay,” said ACC student Lauren Roberts, after discussing her poster with classmates. She explained her understanding of how food insecurity impacts students: “You may not be starving, but you skipped out on a couple of meals this week to pay for something else. You were worrying about where you were going to be able to find your next meal or pay for gas to get to the class, not thinking about ‘I have a test’.”

Food insecurity at ACC and in the nation

Food insecurity is defined as the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or the inability to acquire such foods in a socially acceptable manner.

Guenthner’s students are concerned about food insecurity with good reason. It’s likely a problem at ACC, according to a survey conducted by the office of the dean of students at the beginning of the spring semester. Nearly 55 percent of ACC students surveyed responded yes or maybe to the question “As a student, has there ever been a time when you did not have enough food for yourself or your household?”

Recent research shows that food insecurity is linked to lower grades in college. For example, a study published in October 2014 by Community College Journal of Research and Practice shows that food-insecure students are more likely than food-secure students to have a lower GPA.

According to a 2017 study of hunger and homelessness by the Wisconsin HOPE Lab, 56 percent of community college students experience food insecurity. The study, while not nationally representative, is one of the largest to date, covering 70 community colleges across 24 states.

The Wisconsin HOPE Lab study used the USDA’s six-item food security survey to determine if students were food insecure. Students that answered yes to two or more of the questions fit the definition of a person with food insecurity. The survey consists of questions like “In the last 30 days, did you ever eat less than you felt you should because there wasn’t enough money for food?” and “Did you ever cut the size of your meals or skip meals because there wasn’t enough money for food?”

Jessica Blatecky, a biology professor at ACC, has noticed that some of her students don’t eat regularly. “I think meal skipping is such a common thing with my students. That’s something that I’ve definitely seen,” Blatecky said.

Guenthner said, “In terms of the ACC student population, I’m assuming that we follow national trends, that we probably have a lot of low-income students here that suffer from food insecurity … that’s why a food pantry would be necessary.”

Sofia Bolio and her classmates peer review each other’s final projects at Arapahoe Community College in Littleton, Colo., April 25, 2018. Students created visual documents focused on poverty-related issues that impact the ACC community, such as food insecurity.

Food pantry plans

Food pantries are one way to address food insecurity on college campuses. The number of campus-based food pantries across the U.S. is growing. In 2015, there were 184 registered with the College and University Food Bank Alliance. As of April 2018, there were 626.

ACC does not have a food pantry, but 91 percent of students that took ACC’s survey either agreed or strongly agreed that a student food pantry is needed on campus.

Although there isn’t a food pantry at ACC, there is a food-pantry committee. The informal committee consists of five staff members, mainly administrators from the dean of students office. They are considering ways to assist students with food security.

Last fall, the committee contacted Food Bank of the Rockies. FBR brings mobile food pantries to communities across Colorado including Red Rocks Community College. “We would find a space in the parking lot and then students or staff, whoever was in need, could go through it and move on,” said committee member Tanya Brown, ACC’s care concern and outreach coordinator.

The committee found the mobile pantry model ideal but, unfortunately, it wasn’t available. “Apparently they have limited resources,” said Dawn Zoni, ACC’s dean of students. “We were told it wasn’t an option at this point.”

The committee decided to conduct a survey to determine the need for and interest in a food pantry on campus. They reached out to students at the Student Engagement Fair in January and sent the survey to the student body through email twice this semester. Of the college’s 9,778 students, 329 took the survey.

Meanwhile, Holly Adinoff, coordinator of student organizations and wellness programs at ACC, contacted eleven other Colorado Community College System schools to determine what, if anything, they have in place. Eight of those schools have some form of a food pantry on campus.

ACC’s survey concluded in March, but the results are still being analyzed. According to Brown, one open-response question is slowing down the evaluation of the data. The committee is reading students comments, positive and negative, in an effort to determine “where students fall” on the idea of a food pantry.

Cases of canned and boxed food line storage shelves at Red Rocks Community College. Storage is one of the issues ACC’s food pantry committee is discussing. For example, the group is weighing the benefits of offering healthier options, like fresh produce, against the challenges of storing and distributing items that require refrigeration.

If the committee concludes that a food pantry is needed and desired, they will develop a proposal and take it to ACC’s leadership team and cabinet. These two groups include the executive officers and department directors of the college such as Diana Doyle, president of ACC; Belinda Aaron, vice president of financial and administrative services; and Courtney Lohfelm, executive director of the ACC Foundation.

But Zoni states that there’s a lot more to figure out than just need and interest. Staffing, space and funding need to be addressed as well. “It sounds very easy when you say ‘Oh, let’s start a food pantry.’ But it starts to get complicated when you look at the details.”

Still, most schools in the Colorado Community College System offer some type of pantry for their students.

Food banks at Red Rocks Community College

Red Rocks Community College has a food bank at both its Lakewood and Arvada campuses. Students with a current ID can take up to four items a week. On average, 100 students per week are served. According to Tanner Garren, a student and administrative assistant at RRCC, it costs less than a dollar per student per semester to run. “It’s a system that’s cheap to start up and maintain.”

The food bank has existed for at least a decade and a half, according to Mark Squire, RRCC’S student activities coordinator. It is primarily funded by student fees, which the student government allocates to various campus groups for student-related projects.

Each semester RRCC’s student government votes, and each semester they have chosen to fund the food bank. In the past, the food bank has been authorized to spend up to $9,999 per semester, but current spending is actually closer to $6,000 per semester.

Both Squire and Zoni acknowledge that using student fees for something only some students will take advantage of can raise concerns.

But Squire stated that he’s comfortable with funding RRCC’s food bank from student fees.

“My philosophy, as the student advisor of student government, is that when students tell us that they see a need for something, and they want to spend their money on it, I pursue that,” Squire said. “The students voted to do that with a portion of their student fees.”

In fact, at RRCC, any student may use the food bank. They aren’t required to demonstrate a need. The only qualification to participate is being a current student. “It’s available for them,” Squire stated, referring to the student body. “We want to encourage everybody to participate in it.”

Non-perishable food is offered to students at Red Rocks Community College April 18, 2018. The food bank cart is restocked regularly and made available two days a week.

What now? What next?

The office of the dean of students at ACC already has a few resources in place to assist struggling students. They have recently updated their list of local food pantries in both the Littleton area and the Parker-Castle Rock area. If students go the Student Engagement Center, M2720, with concerns about food, they will be given that list which includes the pantries’ locations, hours and requirements.

The dean of students office can also help people access ACC’s student emergency fund which exists to help students overcome barriers to success at school. Students in need of money to pay for food, gas, a utility bill or childcare may be able to borrow up to $200 from this fund.

Zoni was hoping to get the food pantry proposal done by the end of the spring 2018 semester, but the committee members’ primary responsibilities have kept them busy. As of April 24, the committee had not yet met to discuss the implications of the survey results. Furthermore, budget planning for the 2018-19 school year has already been completed and does not include funds for a food pantry.

Help may be coming, but it won’t be soon.