Woody Guthrie’s focus helps us see 28 ‘invisible’ people — 67 years later

Image via Casey Lansinger

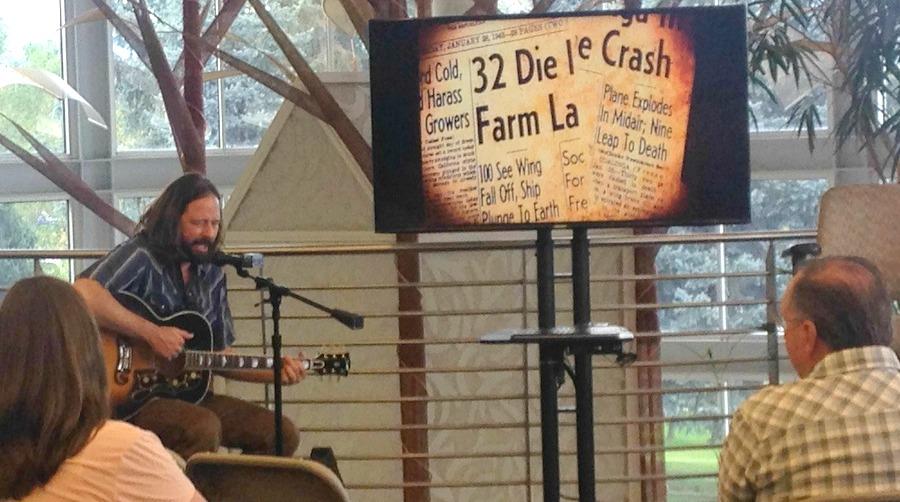

Tim Hernandez shows newspaper headline from 1948.

The sky plane caught fire over Los Gatos Canyon,

A fireball of lightning, and shook all our hills,

Who are all these friends, all scattered like dry leaves?

The radio says, “They are just deportees”

The final stanza of Woody Guthrie’s poem, Plane Wreck at Los Gatos, immortalizes a grave injustice, said Tim Hernandez, poet and author. Finally, 65 years after the event, it was corrected.

As a part of Hispanic Heritage Month, ACC Student Affairs, in collaboration with the Library and Learning Commons and the Writer’s Studio, presented the Colorado Humanities Latino Heritage Live Tour last Thursday: Both Sides of the River: Finding Woody Guthrie’s Deportees.

Author Tim Hernandez told the story to a receptive audience in the library commons followed by a haunting performance of Woody Guthrie’s Plane Wreck at Los Gatos (also known as Deportee) by a Colorado musician, Daniel Grandbois.

The opening story is the saga of Hernandez’ journey to identify by name 28 Mexican nationals who died in a plane crash in 1948. The back story is the account of the 28 Mexicans and why they were on the doomed plane and identified only as deportees.

Tim Hernandez speaks in the ACC Library.

“We make choices when we tell a story of what things to omit,” Hernandez said.

The story made national news, naming the four Americans on board, and identifying the other 28 victims simply as deportees. With the omission of identities considered insignificant, the 28 were buried in a mass grave with a generic headstone in Holy Cross Cemetery in Fresno, Calif. Their families in Mexico never received word of their deaths or where the deportees were buried.

“A story like this is the opportunity to tell stories rather than explore the political aspects of it, Hernandez said. “Many, many books have been written about the politics of the event.

“When we share each other’s stories we find we have much more in common than differences,” he said.

Nameless workers imported by the United States under the Bracero program to work in the fields had overstayed their visas. Along with a number of illegals, they were aboard the ill-fated flight bound for a deportation center near the border. The Jan. 28, 1948, flight never reached its destination.

A fire in the engine of the old DC-3 spread and severed a wing, causing the plane to spiral to the ground in a ball of fire.

All aboard were killed.

A newspaper account that ignored their identities, struck a chord with Woody Guthrie, a famous songwriter / activist of the time. Guthrie had known the sting of anonymity and discrimination as a migrant worker from Oklahoma during the depression. Always treated as outsider by antagonistic California residents and scorned as an Okie, he bitterly resented the treatment of these “invisible” workers.

Guthrie, ill with a neurological disorder, could no longer play his guitar and instead wrote a poem chronicling the tragedy.

The poem lay dormant until Martin Hoffman of Colorado composed music for the words and played it for musician Pete Seeger. Seeger, and many famous musicians, recorded it.

Daniel Grandbois of Colorado sings.

It became a protest song of the 1970s. Although the music kept the story alive, no attempt was ever made to identify the deportees until Hernandez tried.

Hernandez, the son of migrant workers, was researching his book, Manana Means Heaven when he found a troubling newspaper headline: 100 Prisoners See an Airplane Fall From the Sky. When he checked further, Hernandez, unearthed the tale of the forgotten victims of a tragic crash.

Intrigued, he set out in pursuit of the identities of the Mexican nationals aboard. Undaunted by stonewalling in the Hall of Records and the reluctance of the Fresno Roman Catholic Diocese to search old records, he finally connected with the director of Holy Cross Cemetery, who eventually gained access to the death certificates. Comparing the names to the manifest, Hernandez eventually identified every deportee 65 years after the tragedy.

Not content with just knowing who they were, he began a campaign to have the names placed on a respectable headstone.

A massive fundraiser resulted in the purchase of a memorial headstone listing each passenger’s name, including the names of the four Americans.

Finally, in 2013 and with family members of some of the deceased, the new headstone was unveiled.

The 28 Mexicans were invisible no more.

“There are stories of omission out there everywhere,” Hernandez said.

His search is not over, he said. He continues to hunt for families of the victims in remote areas of Mexico. His goal: To tell them about their ancestors, and finally give them some peace of mind and closure.

Caryl Buckstein • Oct 13, 2015 at 11:38 am

Thank you for a powerful story that needed to be told.