Revisited: Striving Against the Odds – Meet Alan Ivar, ACC’s Homeless Student

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Pinnacle revisits a piece originally published on December 14, 2017

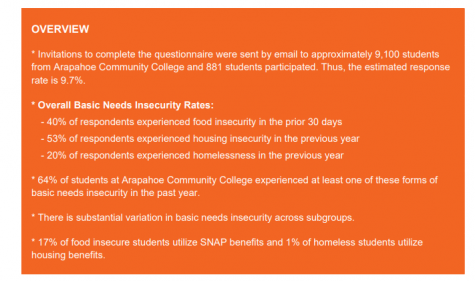

Alan Ivar was the last student we know that was homeless in 2017 attending Arapahoe Community College (ACC). The Dean of Students Javon Brame, spoke to the Pinnacle about a survey conducted in the 2018-2019 school year. According to Brame, only 9.7% of ACC students participated. The percentage showed some students did not want to share their financial situations. The attribution of this percentage showed some students didn’t participate because they didn’t want to share their financial situations.

Homeless students at ACC have struggled during the COVID-19 pandemic. Students from ACC reduced their working hours because they were worried about other issues at home, some ACC Students lost their jobs entirely. At this time, we can all support those Students at ACC who don’t have a home and help them get through tough times. Students can find information about ACC’s COVID-19 response on the website.

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

Carrying crinkly brown paper bags, the remaining students shuffled sluggishly into the brightly lit classroom and took their seats. They placed the bags on the tables in front of them, as reassuring barriers between them and the stage. In the bags were carefully selected items that each student brought in to present as snippets of their lives.

Their painfully pinched faces kept a low gaze while their jittery hands rubbed beading sweat from palms onto dark denim. It seemed no one wanted to go first; no one wanted to expose their life to a group of strangers that met twice a week in this public speaking class where the lighting reminded one of an operating theatre. No one wanted to get cut up first.

In typical arbitrary fashion, the students were called up to the front of the class to give their five-minute presentation. Although tense at first, each student quickly found an agreeable pace; some even enjoyed the brief limelight.

“Hi, my name is Alan Ivar. I’m 19, from Canton, New York, and I am homeless.”

Quiet murmuring breezed through the room as the curly, bronze-haired fellow with the ruddy complexion and iron-rimmed spectacles let his first words sink in. He emanated a sort of taciturn confidence, a serene character, who when done with his presentation was doused with a tidal wave of questions from his inquisitive classmates.

“How come you’re homeless? You don’t look or smell homeless. How do you stay clean?”

“Well, I take care of myself, I dress nicely, and I try to tame this mop,” Alan joked pointing to his head. The young man, with the slightest lisp, did his best to answer all the questions, but the few minutes afforded him weren’t enough to draw a complete picture of his brief, yet eventful life. He stood in front of the class like a young politician running for office.

Alan’s story is the kind that lingers at first but then gets lodged in the folds of one’s memory. His articulate manner and straight posture (the kind your mother always insisted upon at the dinner table) is a testimony to his grounded upbringing. After graduating from high-school in 2016, Alan tried hard to find a job that summer. He sent out applications every day, knocked on doors, but it seemed as though no one was hiring in Canton, a small town of 6000, planted on the southern banks of the St. Lawrence River. Alan began to get antsy. He didn’t want to become a bum and a burden, and after months of no prospective leads, chafing in his parent’s home, Alan decided to act on a whim. He tied a thin sweater around his waist, grabbed his US passport, and headed to the nearest airport where he proceeded to buy a one-way ticket to Calgary, Alberta. Having heard good things about Calgary, and seeing as his biological father was Canadian, Alan figured why not try his luck up North. Of course, he didn’t utter a word to his parents.

“The world is so much bigger than Canton,” says the 19-year-old, “and I had to see it.”

But with only $500 in hand, no luggage, and an off-beam smile, Alan was quickly flagged down by Canadian immigration authorities and brought in for questioning. It was his honest, straight-forward nature, however, that soon had him pouring out a confession. It became clear early on that the young man had no ill intentions; all he wanted was a job. Nevertheless, sneaking into Canada under false pretenses, without the required documentation was not the way to go about the matter. Considered an adult, Alan wasn’t made to go back to Canton, but he had to return to the US, and so was given a choice: Houston or Denver.

“I said, not Houston. So they boarded me on a plane that was headed for Denver,” he recollects, amused. Alan keeps his elbows planted firmly on the table as he speaks. This makes the arm cuff of his black polo-shirt dig into his left biceps, causing him to scratch the spot till it takes on the hue of a pomegranate.

At the age of fourteen, Alan was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome. This makes it hard for him to forge friendships and connect with people. The syndrome is one of several previously separate subtypes of autism that was incorporated into the single diagnosis autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in 2013. Far from the image of Dustin Hoffman in the movie Rainman, Alan doesn’t display any of the typical traits associated with the syndrome; he doesn’t get tongue-tied in social settings, and he doesn’t avoid eye contact when speaking to people. He explains this by referring to himself as being high-functioning autistic.

“I do worry though that I might run out of things to say when I’m talking with someone. It’s those awkward silences that I try to avoid,” Alan describes. “Knowing when a conversation is over is sometimes hard for me.”

It was a mild day in Denver, just before the start of spring when Alan’s plane touched down at DIA. With no baggage to pick up, he breezed through customs. The city was new to him and although he didn’t have any connections or family here he felt determined to make a go of it. Right away, Alan noticed some stark differences between his small hometown in upstate New York, where Kentucky country music blared from bedtruck radios, to Denver, 19th largest city in the country.

“People are people the world over, but Canton is between Vermont and Ohio. I like to call it Alabama but cold.”

And while the climate reminded Alan of home, it was the small things that surprised him when he first got to the Mile-High City. In Denver for instance, most houses are made out of brick, he points out, whereas back home in Canton they’re all made of wood. But perhaps the biggest differences, which surely left an indelible impression on Alan were the busy Denver roads. Not used to big cities, he began to copy Denverites, as they would casually cross roads without paying attention to the white man signal or the red hand signal. In a city like Denver, with more than 4000 stop lights, that type of indifferent behavior would soon prove hazardous. And just a few hours after his arrival, while crossing Broadway and Belleview, Alan was side-swiped by a speeding van. He was subsequently rushed to Denver Health Medical Center where he was diagnosed with a serious concussion and retrograde amnesia. Hospital staff had to keep Alan eight days for in-patient treatment.

“I couldn’t remember much after that. Not having memory is weird–it’s definitely not how they portray it on TV. You’re not like, Who am I?! Who are you?! You’re like scared all the time, and you have nothing to think about.”

Alan describes the anguish he felt during that period as being mentally blind. With time, however, his memory began to slowly trickle back. Little innocuous things like the familiar scent of roasting coffee would trigger his recollection. But most of the time he’d go to sleep at night and by the next morning another missing piece would fall into place. It was in his dreams that Alan would remember things from his past, like the name of his best friend in high school. And although this made him hopeful, he still felt estranged from his own mind.

“Even now it feels as if I’m getting someone else’s memories. I still feel like a different person from whomever it was that got hit by the van. It really feels weird to identify with it.”

Alan’s traumatic experience had him at first battling to determine who he was. It took him three days to remember, and after a call to his parents back in Canton, and some in-house counseling by hospital case workers, Alan ended up homeless for the first time in his life. He was given a list of places where he could go to get a shower, a warm meal and more specific assistance like medical check-ups and how to obtain an ID card. He spent sixteen days roaming the Mile-high City, scrounging up about a week’s worth of food and clothing, taking occasional showers in odd places.

Having exhausted every resource available to him, Alan eventually moved into Urban Peak, a homeless shelter for people aged 15 to 21. He now shares a room with twenty other youths and sees considerable benefits to staying at the shelter. All of the employees at Urban Peak are case management workers, qualified to deal with a range of social issues. He receives three courtesy meals a day there, and tweakers (drug addicts) are not welcome.

“It’s not 100% safe, but I at least I won’t get stabbed for my shoes or something,” Alan says, taking a deep breath and pushing his spectacles higher up the bridge of his nose before continuing.

“There’s definitely a big gap between sleeping on the streets and staying in a homeless shelter like I do. Yes, I’m homeless but I would still consider myself different to real homeless people you might see, like the sunburnt ones with gross beards and torn clothes. I have the opportunity to take a hot shower, I have hot meals cooked every day by volunteers, I have a warm bed.”

Despite living in a shelter, getting an education is important to Alan. He is currently finishing off his general education courses at ACC but hopes to transfer to CU Denver, to study something more substantial like Physical Therapy. But Alan advises against college unless you really know what you want to do because the loans are just so overwhelming.

“I am like $5000 in debt, and interest is increasing as we speak,” he says. According to Alan, a high school graduate could train as an electrician apprentice for two years after which they could earn up to $70,000. No need to fall into debt so early in life. But for those that are certain of their academic path, they should take advantage of any opportunity to save money, such as scholarships and grants.

When Alan’s classmates or even colleagues at work find out that he’s experiencing homelessness, it can become somewhat irritating. He stopped off at the Career and Transfer Center at ACC and happened to mention his condition. The employee immediately got off topic, and went on a tangent trying to provide him with resources and the address to Urban Peak.

“I was definitely appreciative of the gesture, but it’s just gotten to the point where people are like, ‘oh you’re homeless, let me help you with everything.’ And I’m like, ‘thank you but I don’t need it.’ I’m the kind of guy that gets embarrassed by even small compliments.”

Despite seeing homelessness as a national epidemic, Alan doesn’t believe it is the government’s problem. Instead, he sees it more of a social issue. Furthermore, he considers the recent hikes in Colorado’s minimum wage as counterproductive to solving the issue of homelessness. Not every job is worth doing $9.00 for, he argues, but there are jobs worth doing for $4.50. As a result, employers aren’t hiring homeless people because they don’t think they’re worth $9 an hour, whereas the homeless person would be worth $4.50.

“$4.50 an hour is better than not having a job at all,” Alan says.

Undoubtedly, the best thing that’s happened to Alan out here is landing a job. In upstate New York, he worked at a Pizza Hut before being laid off due to overstaffing. This happened shortly after his graduation and he was looking for a job the entire time until he got fed up and came out West. With Denver’s vibrant economy though, it didn’t take him long before he was earning money again. Alan now works at Burger King, and that’s also where he met his new girlfriend, Amiya.

“In New York, not once did I get a single callback for a job. But as I started applying here in Denver, I got a call back within three hours. That just blew my mind—it was amazing.”

Like the very hungry caterpillar that ate its way through a ton of oddities before turning into a butterfly, Alan’s insatiable appetite for life had him fly across the country in search of future prospects. His quest to become a gainfully employed, contributing member of society has finally paid off.