121 A Day

This piece was originally published on Oct. 27, 2017. It was chosen as a finalist in Online Feature Writing by the Society of Professional Journalists for the Region 9 Mark of Excellence Awards.

Content warning: the following piece mentions suicide and contains graphic descriptions.

The week felt like any other.

I woke up, ate my breakfast listening to voices of morning NPR, brushed my teeth, and drove my brother to school, again with NPR playing. As my brother exited the car, a story began on the radio.

“121 people will kill themselves within the next day. . .”

There, parked outside John F. Kennedy High School, my alma mater, I was taken back. Back to 2011. I was a junior at the time. I remember coming home from school one day and receiving a text:

“I can’t breathe. This is too much. I can’t believe this.”

“What? Why? Are you okay? What’s going on?”

“Seth killed himself. I can’t stop crying.”

Seth Trepanier, a JFK sophomore, and friend of many had committed suicide. The school was shaken to its core. Vigils were held during the proceeding weeks and memorials were created and held for the rest of the school year, all the way to May. There was hardly anyone in the school who didn’t know someone who was personally affected by Seth’s suicide. Seth’s younger sister, now a personal friend of mine, also attended JFK at the time. I remember how silent the school was the day following his death. The hallways echoed with the void he had left in the hearts of those who loved him.

Walking through the hallways, even today, I can feel the silence he left. One of my closest personal friends still talks about Seth — a reminder that the ghosts of those we love haunt us long after they disappear.

The story being told over the radio mentioned how Littleton Public Schools have also recently had their share of unfortunate teen student suicides — this year alone 8 students in Arapahoe County have committed suicide. Three students also took their own lives over the course of one emotionally harrowing week this earlier year, two in Arapahoe County and one in Jefferson County.

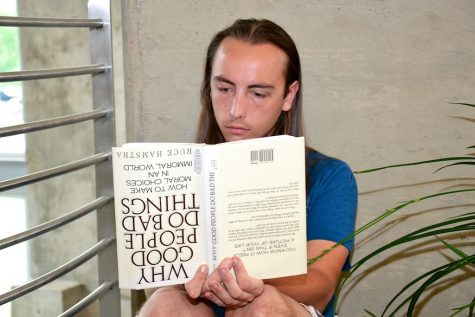

By the time I had arrived back to the present moment, I was walking up the front stairs of the main building of ACC’s Littleton campus. On the second floor’s atrium stood a table covered with various suicide-related resource cards and Colorado Crisis Services (CCS) items. Sitting at the table was a friend and colleague, Ashlyn Stetzel.

With my mind already in a heavy place, I decided to hang out and try to get some stories from passing students. While I waited, Ashlyn filled me in as to how CCS provided most of the materials on the table at no cost. She informed me about why the table was even here — September is Suicide Prevention Month. For two weeks, Student Life had posted four tables total in either the second-floor student lounge or in the atrium, right outside the library.

The tables were there to provide resources, statistics, and other information related to suicide — including gender-focused resources (because in today’s masculine culture where men are encouraged to suppress and avoid their emotions, men experience higher rates of death by suicide compared to women) and sexuality- and age-based resources. It’s understandable — and needed — because, according to a 2015 CDC survey, suicide is the second leading cause of death in peoples aged 10-24. According to the same CDC survey, 14.6% of students surveyed had made an active plan to kill themselves.

No one is untouched by suicide.

For every 25 attempts, one succeeds. Suicide doesn’t discriminate, but it sure as hell seems to pick favorites. For instance, for every four attempts made by an elderly person, one succeeds. In general, men attempt suicide less than women, but are much, much more successful. Middle age white men, in particular, have the highest rate of death by suicide.

Every day, about 121 people succeed in killing themselves. Every day, 121 families are shattered. Every day, 121 flesh-and-blood human beings felt that the only escape they had, from whatever monsters chased them in life, was death.

While I was at the table, a few students agreed to share their stories with me. The fact that I was scribbling down their stories on notepad pages with the CCS hotline number displayed across the top, using a Crisis Center pen, didn’t escape me; It only felt appropriate.

Ashlyn told me about her second cousin who had killed themselves.

A distant uncle of mine had killed themselves as well.

Another student, Bri Fitzegerald, had stopped by to express her gratitude for the table’s presence. “I’m really glad you guys were doing this,” she told us. When I asked about her personal ties to suicide, she informed me of a walk that she had participated in last year to combat suicide, Out of the Darkness.

She also told me of some projects that she had done during her senior year of high school that involved creating zen boxes and small personal gardens for those who are struggling with suicide. She would craft these little one-foot-by-one-foot wooden box gardens with the seeds included; her zen gardens were a bit smaller. For the zen gardens, one of her school’s clubs even 3-D printed some small rakes and donated them to the cause.

Even the students who refused or were reticent to tell me these deeply personal stories could at least confirm that suicide had indeed touched their lives in some way.

Another friend and colleague of mine, Rashid, walked by and, when I haled him over, disclosed three cases to me: one about a high school friend, one about a good friend from Vienna, and one of his roommate, from his days at Ohio University.

It killed Rashid not to know what happened.

Aljosha (pronounced Al-ee-osha — a Greek name which means defender of man — something that I find starkly ironic, considering how this story ends), had gone to the same comprehensive school with Rashid since they were five years old. After graduation and an incredible trip to the Canary Islands, Aljosha went off to SUNY (State University of New York) while Rashid sought his education at Ohio University.

When Rashid traveled home to Vienna for the summer break, he quickly got back together with his old crew and began to inquire about the whereabouts of certain friends. That’s when he heard from a mutual friend that Aljosha had taken his own life.

He apparently flung himself off the Arts building at his University.

Shaken and taken aback by the news, Rashid had to confirm it for himself–so he called Aljosha’s father, a retired colleague of Rashid’s father from the U.N. Rashid described the phone call with the grieving father as one of the most strange and awkward exchanges he had ever had. The father had confirmed the death but didn’t disclose the manner in which the young man died. The father’s stoic and flat response stuck with Rashid, still attempting to cope with the death of his friend.

Rashid then told me of his next friend, Alex. The two were good friends in Vienna during the early 00’s but had lost touch when Rashid was conscripted into the army back in 2005.

At some point, Alex met and fell in love with an older Nigerian woman called Temu. Alex, a kind-hearted generous guy, had helped Temu get away from an abusive Austrian husband; it wasn’t long before the two got married.

Coming home from work one evening, several years later, Rashid heard his name being called by a stranger. When he turned around, he was surprised to see Temu standing across the street smiling, waving at him. She walked over to him, holding a beautiful three-year-old girl by the hand. The little girl had Alex’s snub nose. Rashid and Temu caught up on old times before the conversation turned to Alex.

“Oh, didn’t you hear? Alex killed himself two years ago,” said Temu, matter-of-factly. Rashid couldn’t believe his ears.

“What?! Why?”

But it was her next response that truly floored him.

“Why not?”

Rashid’s eyes fell upon the little girl whose father they were talking about. He didn’t think she should be hearing statements like these, so he said his goodbyes. He hoped to find out more from Alex’s older brother Thomas; He never did. It killed him not to know what had truly happened.

One day while Rashid was surfing around on the net, he found a memorial/obituary profile for his old college roommate, Ryan J. Provil, otherwise known as RJ. Rashid described a lively, highly intelligent kid with an affinity for debating any subject to the point of exhaustion. Ryan was truly a unique individual, he recalled. It had happened in 2008; this was all he knew.

One particular line from that obituary still dances across Rashid’s mind: “. . . died after being struck by a train.”

I drove over the railroad tracks. My mind was heavy and whirling, reflecting on the conversations I had. I recalled the day’s date: September 27. Then another date flashes in my mind: September 25, 2004.

Sure, each year 44,193 Americans die from suicide; and 44,193 sure is a cold, hard number when looked at as just a number. But each one of those 44,193 is a person; a life; a story. They are more than statistics — just ask any of the hundreds of thousands of people they leave behind. Ask me–I’m one of them.

It doesn’t matter that I was ten years old, my brother five. It doesn’t matter that we effectively would be left without parents. It doesn’t matter that we were at a stage in our development that would have deep and profound effects on us for the rest of our lives. It doesn’t matter.

What matters is that on September 25, 2004, I lost a larger part of myself than I could grasp at the time.

The memory is still there, still branded into my mind, finding new and subtle ways to show itself in my life. I can still see the darkness of the twilight sky when I looked out my window when I first awoke. I can still remember the soft light of the kitchen glowing against the stairwell. I still remember calling out to the ether, “Hello?”

I can clearly feel the weight of my mother’s journal, sitting there on the couch begging to be read — begging to spill the secrets my mother had bled across the pages.

I remember some of the details my mother had written. One about wanting her ashes flushed down a toilet, one of wanting a steak knife to slide across her wrists. I remember that she wrote about taking me to the zoo and wishing I would grow up happy.

I can distinctly recall the feeling of time slowing down and racing by, all at once, as I read her words. I traveled through my mother’s hell, page by page.

I remember calling my grandmother at work. She worked night-shifts at a grocery store and was heading home at around the same time.

I remember getting her friend Linda instead. I remember her shocked and distant “What?!” when I told her what I believe had happened; Even though the phone was pressed to my ear, she sounded like she was across the world.

I don’t remember much until my family burst through our apartment door that day, the morning’s sun pushing itself skyward behind them. I remember people shuffling in and out, weeping and crying, patting and consoling. I remember my face being pulled into stomachs and being told how brave I was.

But I wasn’t brave. I was 10.

I remember the subsequent years. The gnawing, aggressive depression that swallowed me without my consent, without my explicit knowledge. I remember the destructive eating habits — entire gallons of ice cream at a time; unchecked calories poured into my body, compounding pound upon pound. I remember the remarkably cruel treatment from my peers when it came to my body’s size.

I remember sitting in class in 7th grade, an internal rage acquiesced by the pressure of the handi-scissors pressed against my neck. I remember the cold bite of the metal as I pushed the sharp ends in.

I remember my best friend at the time getting the teacher. I remember our math teacher, Mr. Melchoir, gently pulling the scissors away from my neck and out of my hands. I remember hating the both of them, the feeling oozing through my veins like ichor. I remember how Mr. Melchoir never mentioned the incident to me again.

I remember years later, cowering alone in my shower, the quintuple-bladed razor head of my freshly acquired shaving kit drawing five perfectly straight beads of blood across my wrist. I remember having several detailed plans. I remember the constant fantasies; the insatiable desire to throw myself off the central, winding staircase of John F. Kennedy.

But mostly, I remember the inescapable wish to end everything I was going through. To escape with the only plans that seemed viable. Waiting it out, suffering and soldiering through my own emotional darkness, was not an option.

Suicide is huge; It is ghastly. It strangles the mind, encompasses it. Consumes it and everything it touches. It feels unspeakable. It screams silently. It is the endless shades of color drained from our cheeks from one night too many contemplating exactly how many pills it will take to render us free. Suicide feels gray, but it’s not. Suicide is orange. It is striking and garish and dark. It is the unnerving sound of leaves scraping as they stroll down the sidewalk beneath us while we stare at the faraway ground, wondering how many seconds it’ll take until we break through the ground and out onto the other side. It is the bolt of lightning that breaks the earth.

I will not act as if I didn’t find comfort in those thoughts. How can you not? How can you not find comfort in the only thing that consoled your pain? How can you not find beauty in the desire?

I will not lie and say that things will work out; as I am well aware, they sometimes don’t. I will not lie and say my life is better now; it’s not. I am though. Despite the thoughts that sometimes creep back in when I’m not paying attention, I am better. Despite a deepening shit-list of life events, I am better.

What I will say is that if you, now or ever, are considering jumping off of that cliff, are considering swallowing that bottle of pills, are considering tightening that rope around your neck, don’t. Don’t eliminate the only chance you have for getting better. How can you be so sure that things will not get better if you don’t stick around long enough to find out?

I can say that there is help out there; I can say that there is support. I can say that you are not alone, no matter what the darkness in your head tells you. I can tell you that I understand the want, the desire, the rush from planning your own death. I can tell you that there’s a good chance you do not want to die, but you wish for the pain to stop, whatever that pain may be.

I can tell you that you deserve to survive. So live.

If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal feelings, or if you are concerned for yourself or a loved one, please reach out to the following resources:

Suicide Prevention Coalition of Colorado

Scott Bright is a second-year ACC student, a Psychology major (with an emphasis on Human Sexuality), as well as the former Editor-in-Chief for The Arapahoe Pinnacle. Still contributing as the Pinnacle's advice columnist, he lives,...

Gina • Nov 7, 2017 at 12:03 pm

Scott, thank you so much for sharing your story. It takes a lot of courage to speak out, and I want you to know that people are paying attention. I’m sorry you’ve been through this and still struggle with these impulses. Be sure to take care of yourself, as you encourage others to do so.